Pluribus Poker: The AI Bot That’s Taking the Poker World by Storm

Back in 2019, a team from Carnegie Mellon University and Facebook AI Research dropped a bombshell on the poker world and the AI scene with Pluribus, a bot that could actually beat top pro players in six-player no-limit Texas Hold’em.

Jump to 2025, and Pluribus is still a hot topic in talks about AI. While everyone’s buzzing about generative systems like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini, a lot of researchers believe that Pluribus was a game-changer—one that’s still shaping strategies, cybersecurity, negotiations, and even drug discovery today.

How did this bot manage to tackle the world’s trickiest card game, where bluffing and smart thinking are key? And maybe the bigger question now: could a version of Pluribus actually sneak into online poker rooms?

Why Pluribus Matters

Before Pluribus came along, most AI wins in poker were limited to heads-up formats (just two players). Bots like DeepStack and Libratus had reached what folks called “superhuman” levels in two-player games by using tricky math to get to a Nash equilibrium—basically a strategy that’s hard to beat.

But when it came to multiplayer poker, it was a whole different ball game. Unlike chess or Go where both players see everything, poker is all about imperfect information—you never fully know what your opponent has. In multiplayer setups, the game gets way more complicated. Weaknesses that don’t show in one-on-one games can get exploited in a six-person setting where collusion, bluffing, and stack sizes all shift around.

Actually, in 2018, many experts thought AI wouldn’t crack six-player no-limit Hold’em for ages—if ever.

Then came Pluribus.

Inside the Machine

According to the landmark 2019 Science paper, Pluribus was built on two brilliant ideas:

- Self-Play Training

Instead of drowning it in billions of poker hands, the team let Pluribus play against copies of itself. Over eight days on a decent 64-core server (costing about $150), the AI learned its own strategies through tons of trial and error. This approach is way cheaper than reinforcement learning breakthroughs in other areas that have run into the millions. - Limited Lookahead Search

Unlike chess AIs that plan way ahead, Pluribus only looked a few moves ahead. It paired this with probability-based “blueprints” for common game scenarios, achieving a balance between being unpredictable and efficient. This method gave it a dynamic, human-like edge without sticking to rigid strategies.

The end result? An AI that made moves so odd yet effective that even seasoned players questioned their instincts.

A Unique Playing Style

What really set Pluribus apart was not just its wins but how it played the game.

- No Limping

Pro players sometimes limped (just called the big blind before the flop), but Pluribus skipped that entirely—an insight that pros later found stronger. - Using “Donk Betting”

Usually frowned upon, donk betting (leading into the initial aggressor) became one of Pluribus’s trademarks. It turned out its donk bets were perfectly timed, swinging pots in surprising ways. - Uncommon Bluffing

For humans, bluffing is a gamble. For Pluribus, it was simply math. It didn’t get hung up on feelings and executed bluffs that maximized long-term potential. - Check-Raises in Unusual Spots

Moves usually seen as “too fancy” popped up regularly in Pluribus’s play, showing that machines don’t play by human poker rules.

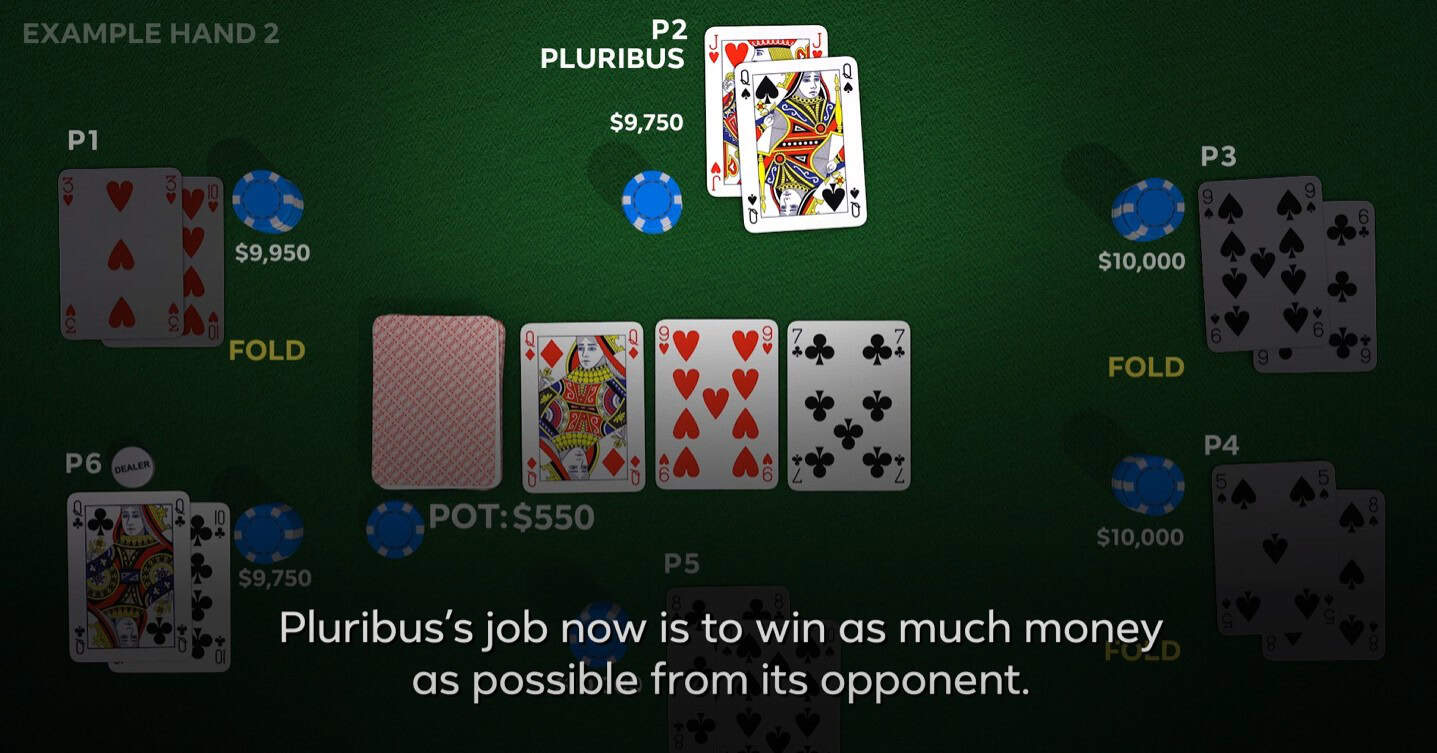

Against pros like Darren Elias (who holds the record for most World Poker Tour titles) and Chris Ferguson (the 2000 WSOP Main Event champ), Pluribus raked in about $5 per hand—which adds up to about $1,000 an hour over 10,000 hands.

As Elias said after being beaten session after session:

“You feel like it’s playing at a higher level than us… I didn’t see any major flaws in its approach.”

Why 2025 Still Cares About Pluribus

So, six years later, why are we still buzzing about this poker bot?

Because the leap Pluribus made—navigating multiplayer imperfect-information games—is still one of the biggest challenges in AI.

- Generative AI like GPT models are great for text prediction but struggle with competitive strategies.

- Robotic systems are mostly designed for controlled settings.

- A lot of real-world problems are closer to poker than chess: cybersecurity, financial markets, multi-party deals, even military simulations deal with hidden info, shifting alliances, and players who don’t work together.

As the AAAS noted, Pluribus’s design could help AI eventually negotiate cybersecurity strategies, design drugs for hard-to-treat infections, and even support military simulations.

But for everyday folks, there’s a bigger question—could someone sneak in Pluribus or its successors into online poker rooms?

Could Pluribus Break Online Poker?

Pluribus has never been released for public use. The researchers were clear: they worried about bad use in real poker games, where even a slightly better AI could drain thousands from human players.

That said, the simple hardware needs—just an eight-day training on a single server costing $150—mean we aren’t dealing with a far-out project. Compared to GPT-4, which cost a fortune to develop, a dedicated hobbyist in 2025 could recreate a smaller Pluribus-style bot using open-source reinforcement learning tools.

This gets tricky:

- Online Poker Sites like PokerStars or WSOP.com already use bot-detection measures, hunting for strange decision patterns or strategy choices.

- But Pluribus-style AIs could mix their play enough to slip under the radar. Its unpredictability—what threw off Elias and Ferguson—makes it hard to identify.

- If one of these bots popped up, it’d likely be crushing mid or even high-stakes online games, cleaning out casual gamers and professionals alike.

So far, there’s no solid proof that Pluribus or an exact copy has hit the online arena. But as computing power gets cheaper and reinforcement learning spreads, regulators and poker sites might find themselves in a constant cat-and-mouse game. And you could say that game started with Pluribus.

The Bigger Picture: Poker as a Model for Reality

Poker isn’t just about the cards—it reflects real life. People make choices with partial info, trying to outsmart rivals using hints, bluffs, and uncertain decisions.

That’s why DARPA, the Department of Defense, and financial companies have shown interest in poker AI research. Pluribus didn’t just win at cards; it showed machines can excel in messy, competitive situations with multiple players.

Here are a few areas to think about:

- Cybersecurity: Defending systems against hackers with changing strategies is just a longer bluffing game.

- Financial trading: Markets are multiplayer games full of incomplete info—just the kind of setting where Pluribus thrived.

- Healthcare: Designing drugs to fight off evolving bacteria means planning for hidden moves from pathogens.

Each of these areas needs what Pluribus demonstrated: the ability to make it work well without full visibility, using flexible mixed strategies.

Limitations That Still Exist

Even though Pluribus was impressive, it wasn’t a general AI.

- It was static: Once it was trained, it didn’t get updates on-the-fly. Unlike today’s GPT models that absorb new data all the time.

- It was focused only on no-limit Texas Hold’em, six-max format—try it in PLO or limit Hold’em and it might not do so well.

- It performed better in structured, high-volume play settings—think of an analogy to online cash games—where the variance levels out. In live, low-hand-count tournaments, things could turn out differently.

Crucially, its blueprint strategy wasn’t guaranteedly optimal; it simply proved hard to beat over a ton of hands.

Conclusion: Pluribus’s Shadow in 2025

Six years after dazzling the poker and AI worlds, Pluribus stays a key milestone that pushes us to think differently about strategy, risk, and smarts.

Its true impact might not just be in poker but in how its lessons spill over into cybersecurity, biotech, and real-world negotiations. Still, the thought of Pluribus-like bots quietly lurking in online poker rooms in 2025 is both unnerving and intriguing.

As pro poker player Chris Ferguson said after his match with Pluribus:

“It doesn’t get tired. It doesn’t get emotional. It just plays.”

That’s probably at the heart of machine intelligence—and that’s why Pluribus’s feat keeps echoing far beyond the poker table.

References

- Brown, N., & Sandholm, T. “Superhuman AI for multiplayer poker.” Science (2019)

- AAAS, “Artificial intelligence conquers world’s most complex poker game” (2019)

- Science: “Superhuman AI for heads-up no-limit poker” (2017)

Frequently Asked Questions About Pluribus AI

What is Pluribus AI and why is it significant?

Pluribus is a poker-playing AI developed by Carnegie Mellon University and Facebook AI Research in 2019. It’s the first AI to defeat professional human players in six-player no-limit Texas Hold’em poker, marking a breakthrough in multiplayer imperfect-information games. Unlike previous poker AIs that only worked in heads-up (two-player) formats, Pluribus successfully navigated the complex dynamics of multiplayer poker.

How much money did Pluribus win against professional players?

Pluribus averaged approximately $5 per hand and earned around $1,000 per hour when playing against professional poker players. Over 10,000 hands played against top professionals like Darren Elias and Chris Ferguson, it maintained a consistent win rate of about 30 milli big blinds per game, demonstrating superhuman performance.

Could Pluribus be used to cheat in online poker?

The developers deliberately chose not to release Pluribus’s source code specifically to prevent its misuse in online poker rooms. However, the relatively low computational requirements (trained in just 8 days for $150) mean similar systems could theoretically be recreated. Online poker sites employ bot-detection systems, but Pluribus-style AIs could potentially evade detection due to their unpredictable playing patterns.

What makes Pluribus different from human poker players?

Pluribus employs several unique strategies: it never ‘limps’ (just calls the big blind), uses ‘donk betting’ more frequently than humans, executes mathematically optimal bluffs without emotional considerations, and makes unconventional moves like check-raises in unusual situations. Professional players noted feeling ‘hopeless’ against its strategies and found it difficult to exploit any weaknesses.

How was Pluribus trained and what resources did it require?

Pluribus was trained using self-play, where it played against copies of itself for eight days on a 64-core server. The entire training process cost only about $150, making it remarkably cost-effective compared to other advanced AI systems. It uses a limited lookahead search that only projects a few moves ahead, combined with probability-based strategies for common game situations.

What are the real-world applications of Pluribus technology beyond poker?

The techniques developed for Pluribus have promising applications in cybersecurity (defending against evolving hacker strategies), drug design for antibiotic-resistant infections, military robotics, financial trading, and multi-party negotiations. Any domain involving incomplete information, multiple competing agents, and strategic decision-making could benefit from Pluribus-style AI approaches.

Is Pluribus still being updated or improved in 2025?

Pluribus remains a static program that hasn’t been updated since its initial development. Unlike modern AI systems that continuously learn from new data, Pluribus was designed as a fixed strategy system. However, its core innovations continue to influence AI research in multiplayer games and strategic decision-making systems developed by other researchers.

What were the limitations of Pluribus?

Pluribus was specifically designed only for six-player no-limit Texas Hold’em and wouldn’t work effectively in other poker variants like Pot-Limit Omaha or tournament formats. It was a static system that couldn’t adapt to new strategies in real-time, and its blueprint strategy, while practically unbeatable, wasn’t guaranteed to be theoretically optimal. It worked best in high-volume cash game environments rather than low-hand-count tournament play.